Readers of this blog know I often find old newspaper articles can offer historical snapshots of our region. So I decided to look at what was being reported in San Diego newspapers exactly 150 years ago to the month. On page 3 of the April 22, 1874 issue of The San Diego Union, within a routine report of the previous night’s meeting of the San Diego Board of Trustees (today’s City Council), it noted board approval for the purchase of a new fire engine. The article quoted one trustee as saying he had “heretofore been opposed to appropriating any money for this purpose” as “he did not think the city was quite ready for it.” (To see the original wording from the board meeting, readers can go online to sandiego.gov/digitalarchives and select 1850-1874 Minutes and Ordinances, p.411, Image 445).

“But now,” the article continued, “the water had been brought into the streets, and several persons had put in fire plugs; others were preparing to do so.”

“Under these circumstances,” the Union article continued in reference to this particular trustee, “he was prepared to modify his opinions; the time had now come when a reasonable expenditure for fire apparatus could properly be made.”

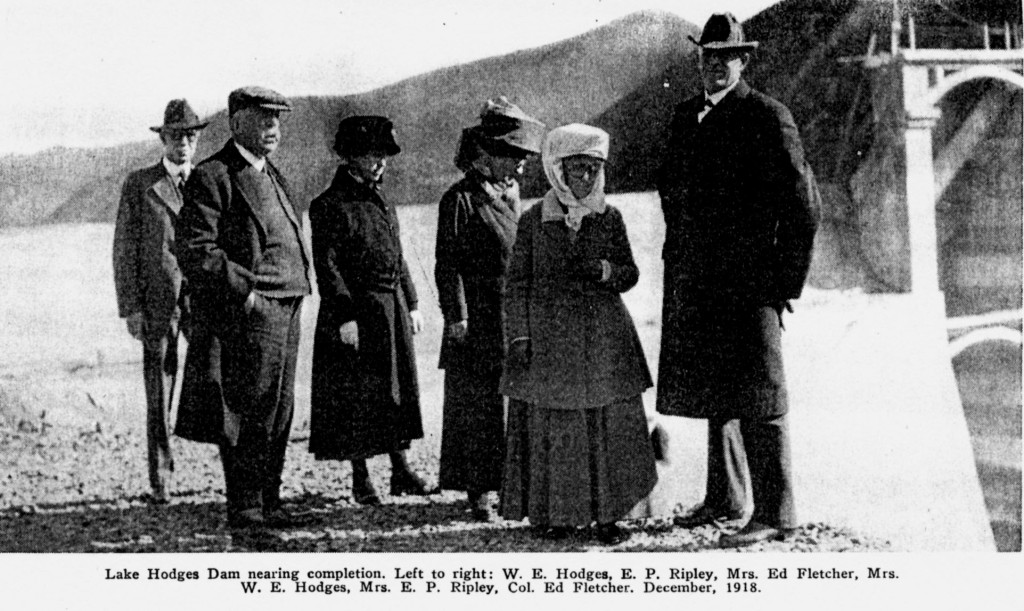

Only a year before, in January 1873, had the San Diego Water Company, the city’s first, been incorporated. It started by digging a well at 11th and B Streets downtown. Over the next decade and a half, under contract to the city, the company would dig 11 more wells in the San Diego River and create two reservoirs to supply a growing city.

And that’s just the start of the story. Or, you could say, if you’ll excuse the pun, the start of the whole dam story.

In addition to historic San Diego newspapers and the San Diego city archives, sources for this post included the 1908 book History of San Diego: 1522 to 1908, by William E. Smythe, the 1922 book City of San Diego and San Diego County: The Birthplace of California, by Clarence Alan McGrew, and the 2023 book, To Quench a Thirst:A History of Water in the San Diego Region, by the San Diego County Water Authority.