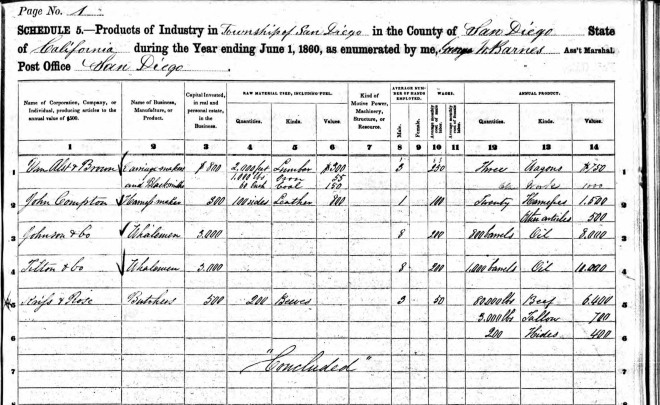

The image above is from the 1860 United States Census for San Diego Township, what we would today call downtown San Diego.

In addition to the population tallies the general public is more familiar with, decennial censuses from early times also included separate schedules for agriculture and industry. These schedules are invaluable for researchers. They also provide snapshots of local life at a certain time and place.

This “Products of Industry” schedule, which covers the one-year period from June 1, 1859 to June 1, 1860, is only one page, and lists a total of 5 businesses. Keep in mind that the city’s total population in the 1860 census was, officially, 731 people. And this industrial schedule was measuring those businesses with annual sales of $500 or more. (Note: $500 in 1860 would be roughly $14,000 today.)

Still, we can be forgiven for thinking there might have been some business owners who chose not to respond to the census takers, especially if it might involve divulging information that would make one subject to paying more taxes. But this data is still worth looking at for what it does show about this small city’s economy at that time.

For example, this enumeration sheet reveals that the most lucrative business in the city of San Diego in 1860 was the sale of whale oil. Two businesses, Johnson & Company, and Tilton & Company, whose businesses are described in column 2 as “Whalemen,” produced 1,800 barrels of oil for the year, which they sold for $18,000. That amount (roughly half a million dollars today), is 62 percent of the value of all the products listed. That says something for the value of whale oil, which was an important lighting fuel for homes and businesses in those pre-electricity days.

The next highest total for a business, $7,500, was the year’s take for Kriss & Rose, butchers who sold $6,400 worth of beef, $700 worth of tallow, and $400 worth of hides to their customers. (Note: the “Rose” in that partnership was Louis Rose, from whom Rose Canyon got its name.)

Then came John Compton, harnessmaker, who sold $2,000 worth of items, followed by Van Alst & Brown, carriage makers and blacksmiths, at $1,750.

While harnessmaker Compton was self-employed, all of the other businessnesses employed wage workers, and the sheet gives their total pay for the year as well. But that’s a story for another time.

Sources for this post included the United States Census Bureau and the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, and the book: Louis Rose: San Diego’s First Jewish Settler and Entrepreneur, by Donald H. Harrison.

Get Updates Automatically-Become A Follower of the San Diego History Seeker

You can get updates of San Diego History Seeker automatically in your email by clicking on the “Follow” button in the lower right corner of the blog page. You’ll then get an email asking you to confirm. Once you confirm you’ll be an active follower.